|

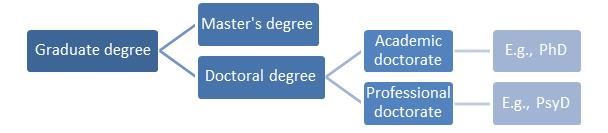

Tamara De Beuf, OG Heldring Institute & Maastricht UniversitySamantha Zottola, North Carolina State UniversityWhether you are browsing the web in search of a PhD program or you are exchanging experiences with fellow graduate students, you have probably noticed considerable differences in how PhD programs around the world are organized. This article features 11 striking differences between PhD programs across the world. Differences in, for example, teaching duties or program duration, will be discussed for three large regions: North-America, Commonwealth Nations and continental Europe. To our knowledge, this is the first article to compare these three regions, as most sources focus on the comparison of two educational systems, such as USA vs. Europe, or USA vs. UK. If you are considering graduate school, we hope this article will help you find the best fit for your academic and personal needs. For current graduate students, insight into the scope of PhD programs may increase understanding of the academic life of fellow PhD students across the globe. Likewise, for faculty, we hope this article encourage awareness of the ‘academic upbringing’ of colleagues, especially in an international setting. Finally, on the administrative level, awareness of the different approaches may contribute to the debate on best practices in designing, implementing and running doctoral programs. Note that this article will not address differences between disciplines or specific universities. Rather, it will provide a broad overview of differences between PhD programs across major regions in the world. What’s in a Name?When familiarizing yourself with graduate degrees, you may be puzzled by the terminology and multitude of abbreviations. Some terms can be used interchangeably, such as ‘doctoral’ and ‘doctorate’; however, this is not the case for ‘doctorate’ and ‘PhD’ (see Figure). Similarly, a master’s and graduate degree do not correspond exactly, as ‘graduate’ refers to all post-bachelor degrees and not only to a master’s. Furthermore, you will encounter PhDs, PsyDs, EdDs, MDs, etc. These are all doctoral degrees, yet different types.

The abbreviation ‘PhD’ stands for the Latin Philosophiae Doctor and refers to ‘Doctor of Philosophy’, which is an earned academic degree. Despite its name, a PhD is not exclusively for students studying philosophy; the rank can be awarded across all academic programs. The word has its roots in the ancient Greek philos (love) + sophos (wisdom/knowing), referring to an appreciation of knowledge rather than a specific study. A PhD is characterized by a strong research orientation; students have to conduct extensive academic research on a chosen subject. After earning the degree, PhDs typically continue as scientists and/or academics. Alternatively, there are professional doctorates that train students to become clinical scientists who are more likely to serve as practitioners than their colleagues obtaining a PhD. A professional (practice-focused) doctorate is common in fields such as medicine and law (i.e., MD and JD), and is also available in psychology as ‘Doctor of Psychology’ (PsyD), and in the field of education as ‘Doctor in Education’ (EdD or DEd).

What’s in a title? Someone who earned his or her PhD can use the title of doctor, abbreviated as Dr or Dr., or use the post-nominal Ph.D., PhD, or DPhil. These titles cannot be used together (e.g., Dr. Jane Doe, Ph.D.), preference should be given to one of them. Someone who is still working on earning a PhD degree is called a doctoral student, doctorandus, or PhD student. In North America, a PhD student becomes a PhD candidate (or doctoral candidate) when he or she has completed all coursework and only has the dissertation to work on. Depending on the program, the student may also have to pass a comprehensive (oral) examination to obtain this particular status. Remember that the use of the title ‘PhD candidate’ is restricted to academic settings. To avoid misrepresentation, it should never be used with clients. Differences across RegionsIn this article, we focus on the research-oriented doctorate degree, the PhD. Each country has its own specifications and customs when it comes to academia in general, and PhD programs in particular. It is beyond our scope to discuss programs of all 196 countries in the world. Therefore, we organize our comparison into three broad regions: North America (i.e., Canada and USA), Continental Europe, and the Commonwealth of Nations (CN). Information concerning the latter primarily pertains to the United Kingdom, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore, and might not apply to other members of the CN. For details on PhD programs in specific countries, we refer to websites such as FindAPhD and Academic Positions. For example, the ‘FindAPhD’ website lists information on 36 countries and how they typically organize a PhD.

In what follows, we compare these three regions on 11 PhD-related topics; from admission requirements and financial matters, to term structure and program duration, to obligations and the final assessment. 1. What does it Take to Get in?Although all regions require good academic performance, typically with a distinction grade, the minimal entry level may differ. In continental Europe, a master’s degree in a related subject is required to be eligible for a PhD program, whereas in the CN and USA, a bachelor’s degree can be sufficient. In the CN, more specifically, a first or upper-second class bachelor’s degree is accepted, which is equivalent to a GPA of 3.3 or higher. Australian programs might additionally ask the applicants to demonstrate research competence (e.g., through peer-reviewed publications, presentations and significant research experience/training). Likewise, in the USA, applicants must hold an undergrad degree in which they acquired significant research experience. A master’s degree can be earned prior to beginning a PhD program or as part of the PhD program. Canadian programs parallel the European requirement of a master’s degree. However, Canadian programs may offer a fast-track for honors undergrad students. A bachelor’s honors degree (Hons) is awarded after completing more rigorous classes, research and a bachelor’s thesis, in addition to the regular bachelor’s program. Nevertheless, for these students, PhD programs will likely be extended with additional master’s level training in the first year. Occasionally, mainly in Europe, a student may be invited by a supervisor to start a PhD, without going through the formal application process. In addition to prior academic degrees, universities will have other requirements to fulfill, such as letters of recommendation, a personal statement, and academic transcripts. Moreover, North American programs require applicants to pass additional examinations (e.g., GRE or GMAT) and in all regions, non-native English speakers have to prove English proficiency via internationally recognized English language tests (e.g., IELTS or TOEFL). For resources on the application process, such as writing a personal statement, we refer to the Graduate School Resources section at the IAFMHS website. 2. What does it Cost?The cost of PhD programs varies by country, student status (domestic/local or international), and type of university (privately or publicly funded). In this paragraph, we present general rules and we strongly advise to research tuition fees of the particular programs of interest. Overall, fees for European PhD programs are low compared to Commonwealth and North American programs. Moreover, many countries (e.g., Finland, Germany, Denmark) offer free doctoral programs at public universities to EU citizens. Non-EU students are typically charged higher tuition fees, In the UK, a PhD student generally pays £3,000 – 6,000 (about USD $4,000 - $8,000) each year and this amount increases to £9,000–14,500 (about USD $12,000 - $19,000) for non-EU (pre-Brexit) students. In Australia, international students pay between AUD $14,000 and $37,000 (about USD $9,900 - $26,000) per year. For domestic students, the cost is lower as they benefit from state subsidies. Unlike the UK and Australia, New Zealand does not charge higher fees for international students; fees vary between NZD $6,500-9,000 (about USD $4,400 - 6,000) per year. Completing a PhD in the USA is most expensive; between US$28,000 - $60,000 annually, with private schools at the upper limit. Public schools offer lower tuition for in-state students (students that live in the same state as the university) versus out-of-state students (students who live in other states or international students). Compared to the USA, Canada is perhaps surprisingly ‘affordable’ with most universities asking an annual tuition fee of CAD $2,000-9,000 (USD $1,500-6,700) for domestic students and between CAD $10,000 and 23,000 (USD $7,500-17,000) for international students. Furthermore, North American PhD programs have additional graduate student fees on top of the tuition fee. Graduate student fees, or ‘compulsory incidental fees’, are used to pay for campus and student services other than instruction (e.g., health-related and recreational services). 3. Funding OpportunitiesIt is possible to obtain complete or partial funding for a PhD program. However, the abundance of funding sources varies widely and, in some cases, comes with stiff competition. Four possible funding sources are bursaries, scholarships, fellowships, and grants provided by governments, universities, hospitals, or foundations. Bursaries and scholarships are similar in that they do not have to be repaid but differ in that bursaries tend to be need-based and scholarships tend to be merit-based. There is a lot of variation in what these funds can be used for (e.g. housing, tuition, textbooks, etc.), their amount and duration, whether the money is taxable, and whether accepting the money comes with any work expectations. These are all critical points to consider when applying for and accepting bursary or scholarships. The website Scholarships for Development provides an updated listing of scholarships, searchable by country, that are available to international students. The other major sources of funding for academic work are grants and fellowships. These funding sources also do not require repayment; however, they are highly competitive. Some grants require the completion of specific research. They are awarded based on a proposed research project that must be completed within a set time frame. With this type of grant, awardees may be expected to meet deliverables throughout the funding duration and to share a final paper or report at the conclusion of the grant. This type of grant is not likely to be awarded to a student. However, it is possible that a student’s advisor may obtain this grant (possibly with the student’s assistance) and use a portion of the funding to pay for their student’s tuition and support their student with a stipend. Other grants, called training grants, fund an individuals’ academic training. Training grants and fellowships are similar in that they are seen as an investment in a future scientist or clinician. Because these funding sources are designed to support a candidate’s training (e.g., coursework, fieldwork), they usually do not require specific output. Each funding opportunity has specific requirements or qualifications, and in some countries, funding might be more difficult for international students to obtain. For example, international students in the USA and Canada will find that government funding is limited and competitive. However, other countries provide more abundant funding to international students.

There are a few other possibilities for funding graduate studies. One is to look for companies that will fund employees who wish to obtain a PhD, in return for a commitment to stay with that company for a set number of years after the PhD is obtained. Another possibility, seen in European countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands, is that universities consider graduate students to be employees. Students are paid a (sometimes tax-free) wage to conduct research as part of their doctoral program, with few obligations beyond research. However, more commonly, PhD students work as tutors or research assistants and in return for this work, universities waive tuition and provide students with an annual stipend. The specifics of this type of arrangement vary (e.g., tax-free vs. taxed stipends), but it is used to fund programs in North America, Continental Europe, and CN alike. An important consideration for this type of funding is the amount of work that will be expected. As we will discuss in the next section, teaching can be time-consuming so taking on a teaching assistantship may require considerably more work and thus delay or put a strain on your own classwork and research. The same is true of research assistantships if they involve research outside the scope of a student’s primary interests or if students are not credited for the work they do. Therefore, it is important for students to be fully aware of the expectations, scope and focus of assistantships. In general, for all funding opportunities, the student must weigh the level of funding, spending options, and output/work requirements carefully. Nevertheless, these funding sources reduce, or even eliminate, the need for graduate students to borrow loans. 4. To Teach or not to TeachThe expectation for PhD students to engage in teaching either as teaching assistants or as primary instructors, varies in programs around the world. Teaching may be a requirement of the funding that students receive toward paying their tuition (see above). When serving as a teaching assistant, students typically work under the primary course instructor and may be expected to grade homework, proctor tests, host study sessions, or engage in other tasks to assist the course’s main instructor. When graduate students serve as primary instructors, they are responsible for creating curriculum and teaching an undergraduate level course on their own. The level of supervision/support that students receive when they are primary instructors varies by university. Some programs provide resources and training opportunities that students can use before they serve as primary instructors. Other programs lack resources and students may find themselves in charge of a class with little to no formal preparation. In general, teaching assistantships are a good experience for students who are interested in careers in academia, especially for those with teaching-oriented career goals. For them, this proof of teaching skills is valuable to include on their CV. Nevertheless, teaching comes with challenges; it is time-intensive and demands a specific set of skills. Therefore, students with less interest in teaching are encouraged to carefully think through the pros and cons of a teaching assistantship. 5. Research first or Research later?

6. Pick and Choose a Supervisor

7. Work those Courses |

although these do not reach the numbers of English-speaking countries.

although these do not reach the numbers of English-speaking countries.

In European and Commonwealth countries, students typically apply to a specific research project or they are invited to a program by the principal investigator, whereas

In European and Commonwealth countries, students typically apply to a specific research project or they are invited to a program by the principal investigator, whereas  The significance of choosing the right

The significance of choosing the right

For students who prefer a short track to their doctor’s title, a PhD program outside of North America would be recommended, especially if they already have a master’s degree.

For students who prefer a short track to their doctor’s title, a PhD program outside of North America would be recommended, especially if they already have a master’s degree.

.jpg)